AI Agents vs. Monitoring Agents: Why the Difference Matters for IT Operations

If you’ve been following the AI headlines lately, you’ve probably seen “AI agents” everywhere—pitched as autonomous systems that perceive context, reason, plan, and take actions with minimal human intervention. The hype is real, but it’s also creating a very specific kind of confusion:

Enterprises already have strong opinions about “agents.” In IT operations, an “agent” has long meant installed software running on servers to collect monitoring data—something many teams avoid for good reasons (security review burden, operational overhead, change control, and scale). When the media says “agents” again, it’s easy to assume it’s the same thing.

It isn’t.

And getting that distinction right helps teams modernize without accidentally reintroducing the pain they worked hard to eliminate—especially in complex middleware estates. If you’re already using an agentless platform like Infrared360 for middleware monitoring and administration, you’re leaning into that precision on purpose.

What a “monitoring agent” is (in the traditional sense)

A monitoring agent is typically a software component installed on each host (or VM/node) that collects metrics/logs/traces locally and ships them to a central monitoring system. A straightforward example is the Amazon CloudWatch agent, which AWS describes as “a software component that collects metrics, logs, and traces” from instances and servers.

Why enterprises avoid monitoring agents

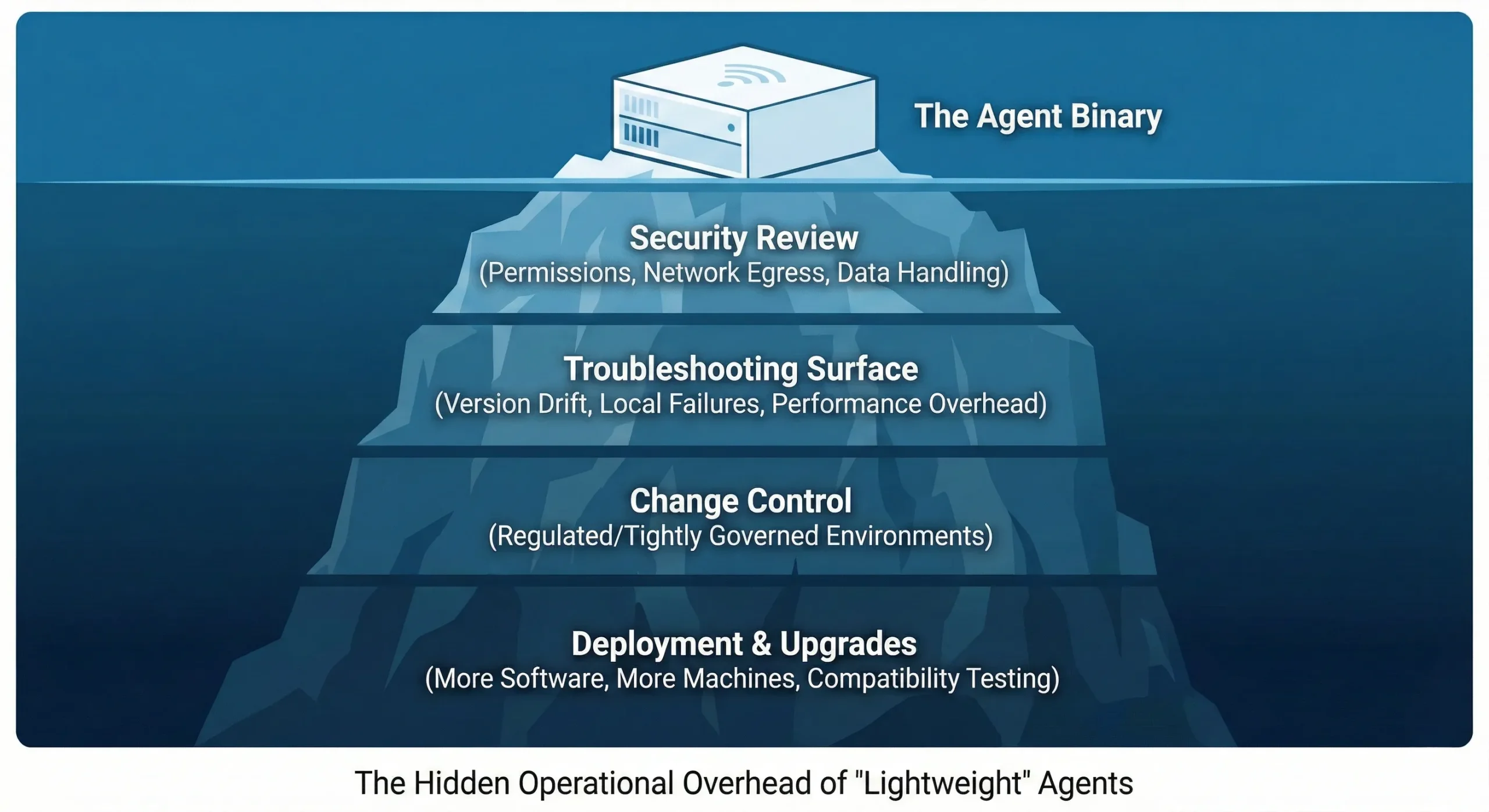

Even “lightweight” agents introduce familiar friction at scale:

- More software on more machines (deployment, upgrades, compatibility testing)

- More change control (especially in regulated or tightly governed environments)

- More troubleshooting surface area (version drift, local failures, performance overhead)

- More security review (permissions, network egress, data handling)

In middleware environments—where stability is everything—those costs compound quickly. That’s why many teams prefer agentless approaches wherever possible.

What an “AI agent” is (in modern “agentic AI” discussions)

An AI agent is usually a goal-directed system that can interpret an objective, gather relevant context, decide on a plan, and then take actions by calling tools/APIs.

A helpful way to reduce confusion is to think in terms of maturity: chatbots focus on answering questions, assistants focus on completing tasks with guidance, and agents are goal-driven systems that can plan and act with delegated authority. Many “agent” products in the market today are closer to advanced assistants with tool use than fully autonomous agents.

In other words, the “agent” label here is less about being installed everywhere and more about behaving autonomously in a loop of observe → plan → act.

In practice, many enterprise “agents” are composite systems—combining an LLM with rules, traditional machine learning, optimization, and policy guardrails—so autonomy is shaped as much by workflow and governance as by the model itself.

One important nuance: AI agents can run centrally or on-device/at the edge—an increasingly important pattern enabled by small language models (SLMs) for latency, cost, privacy, or offline needs (think local coding assistants or on-device mobile experiences). The key point still holds: wherever they run, they’re typically acting as decision + orchestration systems, not telemetry collectors.

The differences that get lost in the hype

1) Where it runs

- Monitoring agent: commonly distributed (on each host) to read local telemetry.

- AI agent: can be centralized or edge/on-device (increasingly enabled by small language models), depending on latency, cost, privacy, and connectivity needs.

Why it matters: Avoiding per-host monitoring agents does not automatically mean you can’t use AI—most AI deployments don’t require installing a monitoring-style binary on every server.

2) Primary job

- Monitoring agent: observation (collect + forward telemetry).

- AI agent: orchestration (decide + coordinate + execute across systems).

A simple mental model: monitoring agents exist to see. AI agents exist to do.

3) Actions and authority

Monitoring agents may support scripted actions in some stacks, but their defining purpose is still collection. AI agents, by design, are about action—opening tickets, triggering runbooks, querying systems, restarting components, correlating signals, and more.

That’s why it helps to separate two layers:

- Seeing (observability): how you collect and interpret signals

- Doing (actuation): how changes get executed safely

If your goal is to keep visibility and middleware administration streamlined without expanding endpoint footprint, that’s exactly what an agentless platform like Infrared360 is designed to support.

4) “Will we end up with agents anyway if we deploy AI?”

Sometimes — but not the same type or in the same way.

Enterprises that adopt AI frequently end up deploying some execution mechanism, but it may look like:

- Tool-calling via existing control planes (automation systems, APIs, Kubernetes, etc.)

- A small number of controlled “runners” (jump hosts / job runners in the right network zone)

- Approval-gated workflows (human-in-the-loop for risky changes)

That’s very different from “install a binary on every server.”

So, if the concern is “we’ll be forced into per-host monitoring agents,” the answer is usually no. But if the goal is “AI should autonomously fix things,” you will need a tightly governed actuation path somewhere—often implemented through BOAT (Business Orchestration and Automation Technologies) platforms and related automation tooling.

A fair skeptic’s point is that even if the LLM “brain” is centralized, actuation still requires an execution path—whether that’s a controlled runner inside the network, an integration service, or “agentless” remote execution over SSH/APIs.

So yes: if you give an AI system the ability to restart components, you’re effectively creating a remote execution capability that must be governed like one. The difference is that this “footprint” is usually about access paths and privileges (who can do what, from where), rather than deploying a telemetry collector on every host.

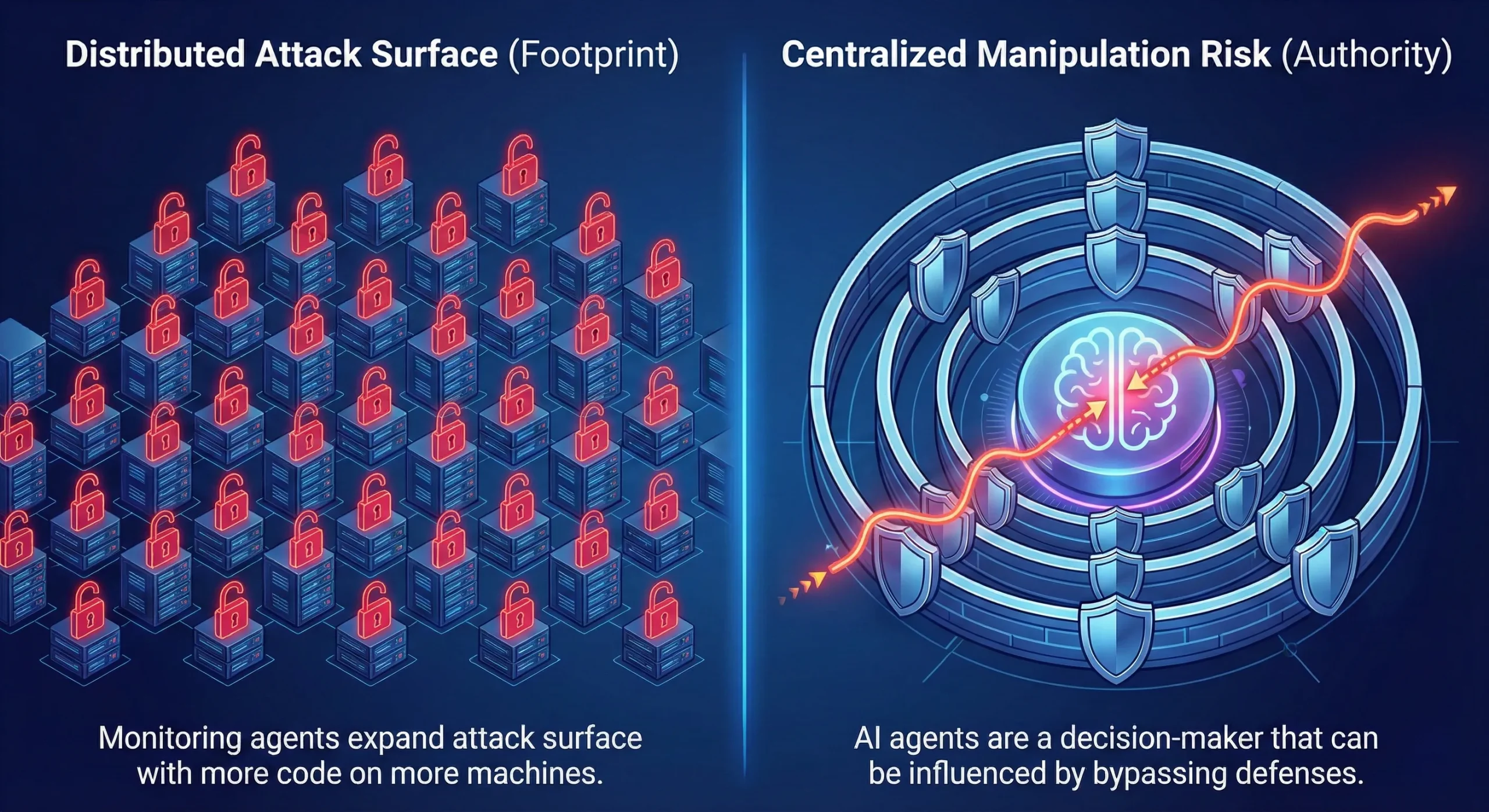

Security comparison: yes, both can introduce risk vectors—but they’re different

Monitoring agents: risk is largely footprint + privilege on endpoints

When you install software broadly across servers, you expand attack surface. Monitoring agents often require elevated permissions to read logs and system state, and they need a route to send data upstream. That can increase:

- Distributed attack surface (more code on more machines)

- Patch and version management burden (at scale)

- Privilege exposure (local access can be powerful)

- Telemetry leakage risk (sensitive data captured or transmitted)

This doesn’t mean agent-based monitoring is “insecure by default”—it means the security and operational cost is real enough that many enterprises choose to avoid it when they can.

Organizations looking to avoid this risk with an agentless platform like Infrared360 get added security with Infrared360’s Trusted Spaces – an integrated RBAC designed to reduce unnecessary exposure by enforcing role/persona-based visibility and action restrictions, so users only see (and can do) what they’re entitled to within the middleware environment.

AI agents: risk is largely manipulation + excessive authority

AI agents introduce a different category of risk: not endpoint footprint, but a decision-maker that can be influenced, paired with tool access that can be over-scoped.

Two widely discussed examples:

- The UK NCSC has argued prompt injection should be treated less like classic code injection and more like exploitation of an “inherently confusable deputy,” pushing teams to focus on reducing impact and designing defensively.

- OWASP’s Top 10 for LLM applications highlights “Excessive Agency”—when LLM-based systems are granted too much ability to call tools or interface with other systems, making unintended actions more likely.

For enterprise governance, many organizations are adopting AI TRiSM (Trust, Risk and Security Management) practices—covering governance and traceability, runtime inspection and controls, information governance, and infrastructure hardening.

Bottom line: avoiding monitoring agents reduces key risk vectors. AI agents may avoid per-host installs, but enabling actuation introduces an access-and-authority problem that must be designed and governed carefully.

A cleaner way to think about it: separate “seeing” from “doing”

If you keep these layers distinct, architecture decisions get much simpler:

- Seeing (observability): favor approaches that minimize endpoint footprint and operational drag.

- Doing (automation): introduce actuation with least privilege, clear allowlists, approval gates where needed, and strong auditability.

Caveat: Modern platforms increasingly blend observability with automation, but it still helps to separate the data-collection footprint from the authority-to-act footprint when evaluating architecture and risk.

That’s how teams modernize operations without quietly reintroducing “agent sprawl”—even as AI becomes more agentic.

Avoid the wrong kind of agent sprawl

As AI becomes more “agentic,” it’s easy for enterprises to accidentally create two kinds of sprawl at once: a growing web of automated actions and a growing footprint of distributed monitoring components. Those are very different risks and costs—and you don’t have to accept both.

A cleaner path is to keep observation lightweight and low-footprint while you modernize the “doing” layer with the right guardrails. In practical terms, that means you can pursue AI-assisted operations (with tightly governed access, approvals, and audit trails) without also deploying a binary everywhere just to get visibility into your middleware estate.

That’s where an agentless platform earns its keep: faster rollout, fewer moving parts on endpoints, less patch/compatibility churn, and a simpler security review surface area—while still giving teams the visibility and administrative control they need day to day.

Learn more about how agentless Infrared360 simplifies monitoring and administration of middleware:

Read the 5 minute paper: Empowering Infrastructure Architects: Ensuring Resilience in Middleware Architectures for Modern Enterprises

or

Schedule a brief call with our experts to discuss how Infrared360 can help you in your middleware environment.

- AWS Documentation — CloudWatch agent described as a software component that collects metrics, logs, and traces. AWS Documentation

- UK NCSC — prompt injection framed as exploitation of an “inherently confusable deputy.” NCSC

- OWASP — Top 10 for Large Language Model Applications (2025) and the risk of “Excessive Agency.”

More Infrared360® Resources